Mahabad – the first independent Kurdish republic

By Mufid Abdulla:

One of an occasional series of articles on aspects of Kurdish history

The first independent Kurdish republic was in Iran. The ‘State of Republic of Kurdistan’ was founded in Mahabad in January 1946 and, although it survived for less than a year, it greatly inspired Kurdish nationalists everywhere.

Abdication of Reza Shah

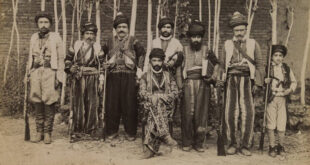

The backdrop to this heroic chapter was the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in 1941, carried out primarily to ensure a ‘Persian corridor’ for US Land-Lease supplies to reach the Soviet Union. The invasion led to the abdication of the pro-Nazi Iranian sovereign Reza Shah, who had a record of brutal repression of the Kurds who comprised around ten per cent of Iran’s population. He tried to ban the Kurdish language and national dress and destroy tribal and other organisations through a programme of executions and deportations. Most Kurds welcomed the advance of the Soviet Red Army into northern Iran and armed themselves with weapons abandoned by the retreating Iranian forces. However, Soviet forces were at this stage committed to upholding Iran’s independence and integrity, and initial Kurdish overtures towards the Red Army met with a cool response. A British commentator noted at the time:

“In the north, Kurdish eyes were turned towards Russia. When the Russians entered Iran in 1941 hopes were aroused that they might assist the Kurdish independence movement, but their very correct behaviour quickly gave the Kurds the impression that any such hopes were vain” (1).

The Soviets did forge links with many of the tribal leaders by arranging for a group to spend a fortnight in Baku, the capital of Soviet Azerbaijan, but they gave a non-committal response to demands that the Kurds be allowed to keep all the rifles that they had accumulated. In May 1942 a meeting between Soviet officials and tribal leaders reached deadlock because the Soviet Union was calling for Iranian officials and regulations to be treated with respect, and seized weapons returned to them, while the Kurds demanded that their language to be used in schools and called for ‘freedom in their national affairs’. As William Eagleton Junior put it:

“Nothing came of the meeting except perhaps a growing realisation on the Soviet side that their security problems were beginning to take on a Kurdish nationalist aspect” (2).

The Komala and Qazi Muhammad

Despite Soviet aloofness at this stage, Allied propaganda denouncing the Axis powers for enslaving other nations and calling for political freedom and national self-determination had a strong impact on many Kurds and this was reflected in the establishment of Komala-I-Zhian-Kurd (Committee of the Life of Kurdistan) in Mahabad in September 1942.

Mahabad was a small town of around 16,000 people situated south of the Soviet sphere of influence. The last vestige of authority of the Iranian government in the town was removed in May 1943 when, in response to sugar rationing, a crowd besieged and destroyed the police station, killing several of its inhabitants. The most powerful figure in the town was Qazi Muhammad a hereditary judge who set up a militia to protect the town from raids by the more predatory roving tribal gangs. Mahabad now enjoyed de-facto independence from the government in Tehran.

Initially Qazi Muhammad was not a member of the Komala. In fact, he was unaware of this secret organisation’s existence for about a year. The Komala was formed by a group of fifteen local citizens, aged from nineteen to fifty, who had sworn an oath never to betray the Kurdish nation and to work for self-government. They represented urban pan-Kurdish nationalism and an alternative to the hitherto predominant tribalism. An article in the first issue of Komala’s magazine vehemently denounced the tribalists:

”You the aghas and leaders of Kurdish tribes, think for yourself and judge why the enemy gives you so much money … they give it because they know it will become capital to delay the liberation of the Kurds and hope that in a few years this capital will create intrigues detrimental to the Kurds” (3).

In April 1943 around 100 members of the Komala gathered on a hill outside the town and elected a central committee to coordinate the work of their growing organisation. Komala’s influence spread through much of northern Iran and also into Iraq. In March 1944, it sent Muhammad Amin Sharifi to Kirkuk to meet representatives of the Iraqi Kurdish Hewa party and a few months later the Sulaymani branch of Hewa sent its representatives on a return visit to Mahabad. In May, the Komala and it Iraqi allies designed a Kurdish national flag – a tricolour of red, white and green with a sun mounted by heads of wheat with a mountain and a pen in the background – as a symbol of the Kurdish nation. Then, in August, an historic meeting of Kurds was held at Mount Dalanpar where the frontiers of Iraq, Iran and Turkey intersect. The delegates signed an agreement, known as the Pact of Three Borders, to support each other in the cause of a greater Kurdistan.

the work of their growing organisation. Komala’s influence spread through much of northern Iran and also into Iraq. In March 1944, it sent Muhammad Amin Sharifi to Kirkuk to meet representatives of the Iraqi Kurdish Hewa party and a few months later the Sulaymani branch of Hewa sent its representatives on a return visit to Mahabad. In May, the Komala and it Iraqi allies designed a Kurdish national flag – a tricolour of red, white and green with a sun mounted by heads of wheat with a mountain and a pen in the background – as a symbol of the Kurdish nation. Then, in August, an historic meeting of Kurds was held at Mount Dalanpar where the frontiers of Iraq, Iran and Turkey intersect. The delegates signed an agreement, known as the Pact of Three Borders, to support each other in the cause of a greater Kurdistan.

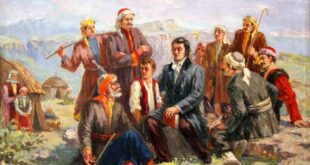

Qazi Muhammad joined Komala in 1944 after the central committee initially turned him down, worried – rightly, as it turned out – that he would take control. In March 1945, the movement went public with the performance of a play attended by many of the local tribal leaders who were now sympathetic. ‘Daik i Nisitiman’ portrayed an old woman being abused by three hooligans (Iran, Iraq and Turkey) and then rescued by the united efforts of her sons. According to an American observer, it made the desired impact:

“… the audience, unused to dramatic representations, was deeply moved, and blood-feuds generations old were composed as lifelong enemies fell weeping on each other’s shoulders and swore to avenge Kurdistan” (4).

Soviet Union pursues oil concessions and backs Kurds

These developments coincided with a shift in strategy by the Soviet Union, now buoyant following its tremendous military victories over Nazi Germany. The Soviet Union wanted to press the Iranian government to grant it oil concessions and decided to encourage separatist movements among the Iranian Azerbaijanis and Kurds as a bargaining chip. Soviet agents flooded into Iranian Kurdistan and tried to control the direction of the Komala.

In September 1945, Qazi Muhammad and a group of prominent Kurds were invited for a second visit to Baku. At a reception with Mir Jafar Baghirov, the head of the Azerbaijan Communist Party, the Kurds made clear their wish for a separate Kurdish state backed by Soviet arms and money. Baghirov told them that their desire for statehood could not be immediately fulfilled because they were dependent on developments in three countries (Iran, Iraq and Turkey) and, in the interim, the aspirations of Iran’s Kurds could be met within an autonomous region of Iranian Azerbaijan. Qazi Muhammad stood up to insist that the Kurds wanted separate autonomy and Baghirov changed his tune.

“Banging his fist on the table, he proclaimed that, as long as the Soviet Union exists, the Kurds will have their independence. Qazi rose to the emotional pitch of his host by declaring that a weak nation would welcome any hand extended to it: ‘Not only will we shake it we will also kiss it’” (5).

Qazi went on the press the case for material support and Baghirov pledged the delivery of military equipment, including tanks, cannon, machine guns and rifles, in “emphatic if general terms” (6). He also argued for the Komala to convert itself into a fully fledged party – the Democratic Party of Kurdistan.

This proposal was implemented soon after the delegation returned to Mahabad. The new party’s manifesto was signed by many leading Kurds who demanded:

“We must fight for our rights … It is for this sacred aim that the Kurdish Democratic Party has been established in Mahabad …It is the party that will be able to secure its national independence within the borders of Persia” (7).

The party’s programme consisted of the following points: the Kurds in Iran should have freedom and self-government in the administration of their local affairs and obtain autonomy within the limits of the Iranian state; the Kurdish language should be the medium of education and administration; a provincial council for Kurdistan should be elected to supervise state and social matters; all government officials should be Kurds; revenue collected in Kurdistan should be spent there; the development of the local economy, public health and education; unity and fraternity with the Azerbaijani people; and the establishment of a single law for peasants and notables.

Barzani arrives

The launch coincided with the arrival in Iran of the Iraqi Kurd leader Mustafa Barzani with several thousand fighters and their families following the defeat of their uprising in Iraq.

Although Soviet officials feared that Barzani was close to the British he soon forged an alliance with Qazi Muhammad who arranged for the Iraqi Kurds to be billeted in Mahabad and other neighbouring towns.

Republic proclaimed

In December 1945 the Iranian garrison in Tabriz, the effective capital of Iranian Azerbaijan, surrendered to the militia forces of the Azerbaijan Democratic Party which proclaimed an Azerbaijan People’s Government and assumed authority for all of eastern (Iranian) Azerbaijan. From the outset it had the trappings of a Soviet-backed regime, including a proclamation of land reform and a secret police force. These events created pressure on Qazi Muhammad to follow suit or risk being outflanked by younger, more militant nationalist elements in Mahabad. On 22 January 1946 he proclaimed the establishment of the Republic of Kurdistan at a meeting in the town centre attended by local citizens, tribal leaders from across the region and three Soviet officers. A national parliament of thirteen members was approved by the crowd, as was the election of Qazi Muhammad as president of the republic.

That same day the new president announced the opening of a high school for girls, a significant reform in a region where the education of girls was practically non-existent. The Kurdish parliament passed laws for universal and compulsory elementary education, with free instruction, clothing, food and textbooks for the children of the poor. Teaching in the Kurdish language was introduced for the first time though, for practical reasons, Kurdish textbooks only became available shortly before the fall of the republic.

The Soviet influence was more subdued here than in Azerbaijan. The Kurds hung portraits in Stalin in government offices but there was no significant repression and no secret police. In an interview with a French journalist, Qazi Muhammad expressed a conciliatory approach to the Tehran government:

“The Kurds would be satisfied if the central government decided really to apply democratic laws throughout Iran and recognised the laws now in force in Kurdistan concerning the education of the Kurd and the autonomy of the local administration and the army.

“The situation in Kurdistan is very different from that in Azerbaijan. Our country has never been occupied by Soviet troops and since the abdication of Reza Shah, neither the gendarmerie nor Iranian troops have penetrated into Kurdistan. We have therefore practically been living in independence since that time. Further we shall never tolerate foreign intervention wherever it comes from. The question of Kurdistan is a purely internal affair which should be settled between Kurds and the central government” (8).

Indeed Soviet material support was much more limited than many Kurds had hoped for: a vital printing press arrived, together with a supply of rifles and pistols but there were no tanks.

Soviet Union and tribal leaders backtrack

Although the Kurds did not realise it, the fate of their republic was sealed the moment the Soviet Union pledged to withdraw all its forces from Iran in return for the prospect of oil concessions. Shortly after this the fledging Azerbaijan regime in Tabriz signed an agreement with Tehran formally reverting to Iranian sovereignty and leaving the Kurds effectively isolated. The Republic of Kurdistan had established an army of around 13,000 fighters, including the big contingent of Iraqi Kurds under the command of Barzani. The Kurds even contemplated a southern offensive against Iranian forces but this plan was shelved in response to Soviet warnings.

When Qazi Muhammad began negotiations with Tehran it was from a weakening position, especially because many Kurdish tribal leaders were now distancing themselves. They were motivated by a variety of factors, including historic hostility to Russia, religious hostility to the atheist Soviet Union, concern about the economic viability of the republic, resentment toward the Iraqi Kurd Barzani (who was one of the republic’s four generals), annoyance that the republic’s president was not himself a traditional tribal leader and finally a shrewd sense of where the wind was blowing and a desire not to be on the losing side. In December the Iranian army entered Tabriz and the pro-Soviet regime collapsed instantly, with most of its leaders fleeing across the border. Although Qazi Muhammad’s war council had pledged to fight the Iranian army, many tribal chiefs and notables were changing sides and it was decided not to resist the occupation of Mahabad.

In the early hours of March 23 1947, Qazi Muhammad, his brother Sadr Qazi, and his cousin Sayf Qadr were hanged at dawn in the town centre where the republic had been proclaimed just ten months before. It was a vindictive act by the Tehran regime against the leaders of a popular, progressive and largely peaceful nationalist movement.

An American correspondent wrote:

“… while terrorism reigned unchecked in eastern Azerbaijan, in Kurdistan there were few if any political prisoners and only one or two cases of what may have been political assassination; though a number of Kurds not in sympathy with the regime did flee to Tehran. In the streets of Mahabad one could hear radio broadcasts from Ankara and London, while in Tabriz to listen to these brought the death penalty … the net result was to make the regime popular at least among the citizens of Mahabad who enjoyed their respite from the exactions and oppression they considered to be characteristic of the central Iranian Government” (9).

As the historian David McDowall put it: “The Qazi trio perished because they personified the nationalist ideal” (10).

While the Iranian regime succeeded in cowing Iran’s Kurds for a generation, they also created martyrs who would inspire the Kurdish struggle in Iraq and elsewhere. The tradition of nationalist, as opposed to tribal, struggle became entrenched in the Kurds’ collective consciousness.

References

- The Kurdish Question, WG Elphinston, Royal Institute of International Affairs,1946

- The Kurdish Republic of 1946, William Eagleton Jr, Oxford University Press, 1963

- A Modern History of the Kurds, David McDowall, IB Taurus, 2004

- The Kurdish Republic of Mahabad, Archie Roosevelt Jr., Middle East Journal, no 1, July 1947

- Eagleton

- Eagleton

- McDowall

- Eagleton

- Eagleton

- McDowall

History of Kurdistan

History of Kurdistan