Russian researchers have discovered the ruins of a 4,000-year-old settlement that rose from the ashes of the Babylonian empire in Iraq.

The ‘lost city’ was discovered on June 24 in Iraq’s Dhi Qar Governorate, which was once the heart of the ancient Sumerian empire, which is said to be one of the world’s first civilizations.

‘The discovered city is an urban settlement in Tell al-Duhaila, located on the banks of a watercourse,’ Alexei Jankowski-Diakonoff, a researcher at the St Petersburg Institute of Oriental Manuscripts and head of the excavation, told Al-Monitor.

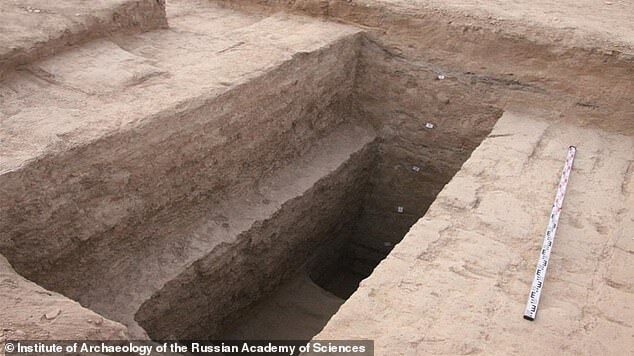

The team uncovered numerous artifacts—including a rusted arrowhead, traces of tandoor stoves and clay camel statues dating back to the early Iron Age.

They also found the remains of a temple wall about seven feet tall and 13 feet wide and an ancient port where both river and sea vessels would have anchored.

‘This recent discovery is of paramount importance because it introduces the world to one of the Sumerian cities overlooking the seaports,’ Gaith Salem, a professor of ancient history at Al-Mustansiriya University, told Al-Monitor.

‘Most cities used to have a view to the sea but have turned today into a vast desert.’

Tell al-Duhaila is home to hundreds of historically important sites, including the Great Ziggurat of Ur, and has withstood the mass vandalism, looting, and intentional destruction of ancient sites in Iraq that started in the early 1990s.

It’s also near the city of Eridu, where, according to Sumerian legend, all life began.

Jankowski-Diakonoff’s team began its research in the region in 2019, with the actual field work starting in April 2021.

‘The city could be the capital of a state founded following the political collapse at the end of the ancient Babylonian era,’ Jankowski-Diakonoff speculated, around the middle of the second millennium BC.

‘Researching the cities of southern Mesopotamia at the end of the ancient Babylonian era — and the Tell al-Duhaila site in particular — opens the secret of an unknown page in the history of the oldest civilization on the planet,’ he said.

The site appears to offer evidence of the earliest agricultural use of silt in Mesopotamia, predating the emergence of the Sumerian civilization.

Silt is granular soil left behind on riverbanks—its presence allowed crops to be grown in the dry, arid region eventually known as the Fertile Crescent.

Because the site has been left untouched all this time, Jankowski-Diakonoff told Al-Monitor, he expects to find cuneiform documents ‘in an undisturbed archaeological context’.

Jankowski-Diakonoff said based on the design and the huge blocks used to create the wall, it was most likely built during the ancient Babylonian era.

‘It mainly reflects slave culture,’ he said. ‘The Neolithic period and Early Copper ages.’

Dhi Qar antiquity director Amer Abdel Razak said land surveys date habitation on the site to the ancient Babylonian era, but it might go back further given the pottery pieces and statues the Russian mission found.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE: Brutal 6,200-Year-Old Massacre Shows Humans Have Sucked for a Really Long Time

An international consortium of experts from universities and museums will descend on Dhi Qar in October.

Salem urged resources continue to be devoted to archaeological work in the region, ‘to unearth the treasures of history, which are not important only to Iraq, but all humanity.’

History of Kurdistan

History of Kurdistan