By the time Saddam Hussein’s Anfal campaign ended in 1988, hundreds of thousands of Kurds had been imprisoned or killed. Kulajo, a village of some 300 people, alone lost almost half of its population.

A 12-year-old Kurdish boy who has just escaped execution limps slowly along a desert trail near Iraq’s border with Saudi Arabia, blood seeping from bullet holes in his back and shoulder.

Seriously wounded and alone at night, his chances of survival seem slight. He reaches two trails in the desert, and his decision to take one of them will save his life.

Teimour’s story proved beyond doubt that Saddam Hussein’s regime carried out a secret programme to exterminate Iraq’s rural Kurds

What happens next to Teimour Abdullah Ahmed will create one of the iconic stories of Anfal.

Furthermore, Teimour’s experience proved beyond doubt that Saddam Hussein’s regime was carrying out a top secret programme to exterminate Iraq’s rural Kurds.

The Iraqi army destroyed some 2,500 Kurdish villages during the six months of Anfal. Kulajo was a close-knit community where villagers enjoyed tending to their animals and cultivating their lands. Yet that lifestyle ended when Iraqi soldiers destroyed the village in April 1988.

Kulajo, a small village of 300 souls, far to the north in Iraq, was one of thousands of Kurdish villages targeted during the regime’s Anfal campaign which led to the deaths of up to 182,000 Kurds.

It was one of many remote communities that gave unstinting support to the Kurdish resistance. But as the peshmerga grew stronger, the Iraqis began to step up their harassment of the villages.

If we’d known what was coming we would have killed ourselves

Much of rural Kurdistan was declared a prohibited zone which meant that any Kurd found in these areas could be shot on sight.

Peshmerga, however, ignored the increasing risk of helicopter attack and continued visiting Kulajo where they found food, shelter, ammunition and recruits.

The Iraqi regime punished those villages who helped the Kurdish resistance. Aircraft overflew the area regularly, attacking buildings, cars, tractors and people. Nevertheless, these communities continued supplying the Kurdish peshmerga fighters with food, weapons, shelter and recruits.

When the village was attacked in April 1988 as part of the regime’s genocidal Anfal campaign against Kurdistan, there was pandemonium.

‘People were running everywhere,’ said Amna Ali Aziz who lost 15 members of her family during Anfal. ‘Babies were born and abandoned. Two babies were left in a basket and their bodies found a year later.’

Audio Player

‘If we’d known what was coming we would have killed ourselves,’ says Ismet Mohammed Mahmoud. She lost, a son, two sisters, a brother and 26 members of her family during Saddam’s campaign to crush the Kurds.

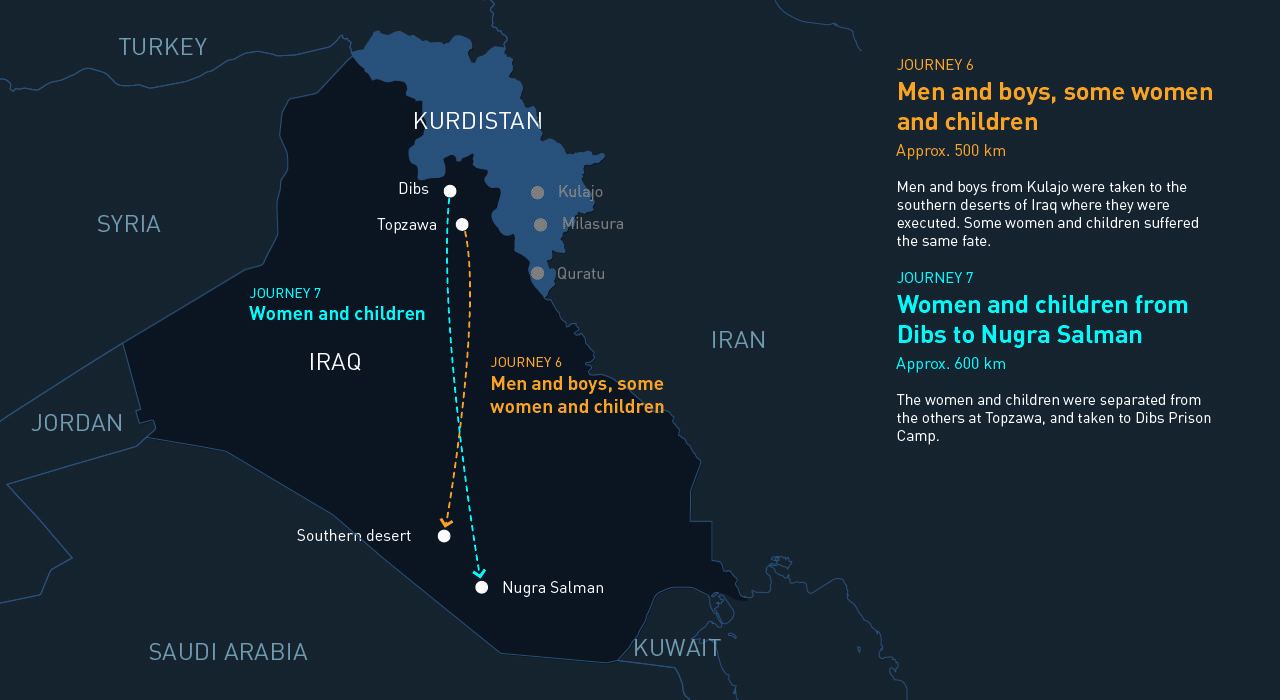

Teimour, Ismet and Amna were among the 300 villagers from Kulajo who had been rounded up by the Iraqi army and first taken to Qoratu, an army fort 40km to the southeast. There they were forced to abandon all their belongings, and moved westwards to Topzawa, an army camp on the outskirts of Kirkuk.

The Iraqi Anfal attack on Kulajo in April 1988 was barbaric. Villagers fled in panic and some left their babies behind in the confusion. Houses were bulldozed and herds of animals escaped into the wild. Many villagers were imprisoned in the south of Iraq and many Kulajo men, women and children were killed in execution pits.

They were then divided into two groups. One, comprising mainly women and children, was moved to Dibs 20km to the northwest.

The other, which included Teimour, his mother and sisters, was ferried from Topzawa to the deserts west of Samawah, 450 miles to the south. They rode in white and green windowless trucks, each carrying about 30 people, with no ventilation or food and virtually no water.

There were a series of pits filled with women and childrens’ bodies, with bulldozers shovelling sand over them. The Iraqis forced us into them

‘Two girls died because of lack of food and air,’ says Teimour. Another woman gave birth during the journey inside the vehicle.

Teimour managed to untie the rope binding his hands and remove the blindfold from his eyes before they arrived at their destination. It was evening when the vehicle stopped and Teimour was gripped with horror when the door opened.

‘I saw there were a series of pits filled with women and children’s bodies and bulldozers shovelling sand over them,’ he says. ‘They forced us into the pits and some people began lying down whilst others sat.’

Almost immediately, soldiers wearing red berets started firing into the pit. Teimour ran to one of them and hugged him. ‘I begged him in Kurdish, “Don’t shoot, don’t kill us. What did we do? Why are you killing us?” He didn’t understand. His eyes were full of tears. It was as if he’d been forced to do this.’

I begged him in Kurdish, “Don’t kill us, what did we do?” He didn’t seem to understand but his eyes were full of tears

Teimour was hit in the shoulder and pretended to be dead but saw exactly what was happening around him.

‘They were shooting at a pregnant woman and her blood and brains were spurting out of her head,’ he says. ‘My mother, my three sisters, my aunt and my cousins – there were eight or nine boys and girls – were all with me in the trench.’

The story of TEIMOUR ABDULLAH MOHAMMED is one of the iconic stories of Anfal. He was the first person to provide an eyewitness account of the mass killing of Kurdish civilians by Iraqi death squads. His life was saved by an Arab bedouin family who risked the lives of their entire tribe to protect a little boy from Saddam Hussein’s secret police.

‘My sister’s hand was bleeding. Her name was Lawlaw. My younger sister, Snur, who was about three, was also hit. A bullet had struck an artery and her blood flowed like water. I saw that my mother’s headscarf had been blown off and bullets had struck her head.’

‘My uncle’s wife shouted my mother’s name when she was hit. Those were her last words,’ says Teimour. ‘The trench shook with the sound of shooting and blood was running down my arms and chest.’

The trench shook with the sound of shooting and blood was running down my arms and chest. I was scared and didn’t know who was alive

Teimour thought he was about to die. The soldiers left talking amongst themselves. He tried to escape and crawled out of the pit. ‘I was scared for my life and didn’t know who was alive. I rolled over bodies. There was so much blood, as if rain had turned the ground to mud.’

He spotted a landcruiser moving around the trenches checking for survivors. He hid in a mound of sand and then moved from trench to trench before finally losing consciousness.

After crawling out of an execution pit in southern Iraq, in which his mother and other family members lay dead, an 11 year old TEIMOUR ABDULLAH MOHAMMED fled deep into the desert. Covered in blood, he was surrounded by barking dogs, which alerted their owners to his presence. This Bedouin Arab family would later risk their lives to save him from the Iraqi secret police.

When he woke up he saw a little girl who was still alive. ‘Let’s get out,’ he told her.

‘I won’t leave my mother and I’m scared of the soldiers,’ she said.

Teimour woke up in the pit of dead bodies and saw a little girl who was also alive. “Let’s get out” he said. “I won’t leave my mother and I’m too scared of the soldiers” she replied. He never saw her again

Teimour left her in the pit and fled. He realised that he and the little girl were the only ones still alive after the massacre.

After walking on his own for hours in the pitch-black night, Teimour saw lights ahead, heard the sound of barking dogs and then spotted the ghostly outline of Bedouin tents. The dogs surrounded him and stopped him in his tracks. Bedouin shepherds came out to investigate.

Women and children from Kulajo village were imprisoned in Dibs, near Kirkuk. There were no facilities for pregnant women, and many gave birth in open prison halls. With no blankets for the babies, women were forced to rip up their undergarments to use these instead.

‘My uncle Ghanm went with a torch and saw a child covered in blood,’ says Fadhil Al- Zayadi, a small boy at the time whose father owned the tents and who is now a close friend of Teimour’s. ‘The dogs seemed to be protecting the child as if God wanted to protect his life.’

‘We took off his clothes and saw he had a bullet wound in his back and his shoulder. We couldn’t call a doctor because this was a serious crime under Saddam. We’d all have been killed if we’d been caught sheltering him,’ says Fadhil.

He was deeply traumatised and having witnessed the execution of his immediate family feared the worst for the rest of the village. The women and children from Kulajo, who were transported to a military camp in Dibs, a small town northwest of Kirkuk, were more fortunate, however.

The women and children of Kulajo village were transported from the Dibs prison camp to Nugra Salman prison in long buses. On arrival in Topzawa, near Kirkuk, a transitory stop, they only saw old men imprisoned there. At this moment they realised the young and adult males from their village had been taken into the desert and killed.

The women and children from Kulajo, who were transported to a military camp in Dibs, a small town northwest of Kirkuk, were more fortunate, however.

There they were given some food and helped by the local Kurdish community. But disease was rife and scores of children died. There were no medical facilities and the families held captive there struggled to survive.

Many women gave birth in squalid conditions.

Two months after the attack on Kulajo, the women and children from the village were loaded onto long windowless buses and driven south past Baghdad.

Their destination was Nugra Salman, a desert prison camp in southern Iraq. A sign on the gate read “Welcome to Hell”

‘We got to a dirt road and stopped. We thought they were going to kill us so we started pulling our hair and crying,’ says Ismet, Teimour’s aunt. ‘One of the soldiers got off and said, “We’re taking you to a desert camp.”’

Their destination was Nugra Salman, a desert fortress which had served as a prison camp for enemies of the Iraqi state since the 1940s. One of the signs on the gate read “Welcome to Hell.”

When the buses arrived only old men who had been separated from them at Topzawa were there to greet them. ‘They’d taken the young ones and killed them,’ says Ismet. ‘Everyone searched for their families. It was a dark day: we were like lambs separated from sheep.’

In the summer heat, they were deprived of water. ‘Every two days they’d pass a little water through the bars in a bowl or bucket. It was like sewage. We drank it and were immediately sick,’ says Amna. ‘They gave us some dry, hard bread and some bitter tea in the morning.’

Once the Iraq-Iran war finished, Saddam Hussein attacked 70 Kurdish villages south of the Turkish border with poison gas. The peshmerga had no choice but to stop fighting and retreat into Iran. Kurdish prisoners were freed from Nugra Salman prison, but then forced to live in guarded settlements

All the women in the prison were regularly beaten because they were “wives of peshmerga.”

‘I had both my girls in my arms and was hit in the face with a cable,’ says Ismet. ‘I didn’t know whether it was night or day or what happened to the babies in my arms. After about an hour I regained consciousness.’

“When someone died in Nugra Salman their corpses were put in a wheelbarrow and buried in shallow graves,” says Hamid, “And afterwards dogs dug up the bodies and ate them”

People died most days. Hamid Karim Kakil, aged 55 during Anfal, was assigned by the Iraqis to bury the bodies in the wasteland around Nugra Salman.

‘When someone died, policemen accompanied us,’ says Hamid. ‘We put the corpses in a wheelbarrow, dug for half a metre and covered them with soil. After we left, the dogs dug up the bodies and ate them.’

After Saddam’s defeat in the Gulf War in 1991, the Kurds rose up to take control of Kurdistan but within three weeks their uprising was crushed. Once again, Kurds feared for their lives and fled to Iran and Turkey. Kulajo’s inhabitants realised their nightmare was far from over.

‘There were dogs everywhere,’ says Amna. ‘They ate a lot of flesh.’

Meanwhile, the Anfal campaign was reaching a climax. The Iranians were driven out of Iraq and the peshmerga defeated by a terrifying Iraqi chemical weapons onslaught which forced them to seek sanctuary in Iran.

The Kurds who had survived Anfal no longer posed a threat to the Iraqi government and, in September 1988 with the Iraq-Iran now over, Saddam felt confident enough to order their release from Nugra Salman.

They were not allowed to return home, however, and moved to a government settlement near Kalar, 20km east of Kulajo.

Policemen assigned us the job of burying the bodies. We dug for half a metre and covered the corpses with soil. After we left, the Iraqis’ dogs dug them up and ate them

After Saddam’s defeat in the Gulf War in 1991, however, their lives changed dramatically once again.

The Kurds rose up to take control of Kurdistan but just three weeks later their uprising was crushed by the Iraqi army.

More than one a half million Kurds, including villagers from Kulajo, fled in panic to Turkey and Iran.

After coalition forces established the safe havens in Iraq, Teimour’s surviving family returned to Kurdistan. They were shocked by what they found in Kulajo. The village was in ruins and empty. Living from a tent, they gradually began to rebuild their lives. Many of his relatives however opted to give up their rural existence preferring to live in the towns.

More than 20 years after his ordeal in the southern Iraqi desert, TEIMOUR ABDULLAH MOHAMMED is reunited with the Bedouin Arab family who saved his life. They take him to the site where his family were shot dead, and he explains how this traumatic event has shaped every minute of his life ever since.

Despite the dangers the Bedouin family faced in southern Iraq, they treated Teimour like a son and helped smuggle him back to Kurdistan in 1991.He then moved to the United States when it became clear that Iraqi agents were once again on his trail. After the last Iraq war in 2003, he returned to his homeland.

Twenty-one years after surviving execution, Teimour was reunited with the Bedouin family in Samawah who had risked their lives to save his. The family guided him to the desert site where Teimour had been gunned down with his close relatives. There, he discovered a garment riddled with bullet holes worn by one of the babies who had been killed.

From a mass grave I found a new life and new brothers, fathers and mothers. It’s like my heart is beating in two bodies

‘Many want to distance themselves from these stories,’ says Teimour. ‘They cannot handle this much anxiety and sorrow.’

‘But from a mass grave I found a new life and found new brothers, fathers and mothers. It’s like my heart is beating in two bodies. I now have family in the north and south of Iraq.’

Teimour no longer lives in Kulajo and the village where 300 people once lived is now home to just a handful of families. Sadly his tragic story deepened in adulthood: in January 2015 he was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment by a court in the Garmiyan region of Iraq for being an alleged accomplice to the murder of a policeman.

Kulajo village

Kulajo Village in the Garmiyan region would often host visiting peshmerga forces and provide shelter and supplies. This made the village a target for Saddam Hussein, and in April 1988 Iraqi forces arrested and imprisoned Kulajo’s inhabitants. Half of them died during Anfal.

History of Kurdistan

History of Kurdistan