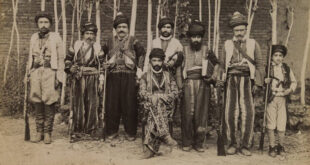

Simko Shikak (born Ismail Agha Shikak 1887 – 1930, Kurdish: سمکۆی شکاک, romanized: Simko Şikak) was a Kurdish chieftain of the Shekaktribe. He was born into a prominent Kurdish feudal family based in Chihriq castle located near the Baranduz river in the Urmia region of northwestern Iran. By 1920, parts of Iranian Azerbaijan located west of Lake Urmia were under his control. He led Kurdish farmers into battle and defeated the Iranian army on several occasions. The Iranian government had him assassinated in 1930. Simko took part in the massacre of the Assyrians of Khoy and instigated the massacre of 1,000 Assyrians in Salmas.

Family backgroundEdit

Political life

There are different and conflicting views about Simko among Kurdish historians. After the murder of Cewer Agha, Simko became the head of Shikak forces. In May 1914, he attended a meeting with Abdürrezzak Bedir Khan who at the time was a Kurdish politician supported by the Russians. The Iranian government was trying to assassinate him like the other members of his family. In 1919, Mukarram ul-Molk, the governor of Azerbaijan devised a plot to kill Simko by sending him a present with a bomb hidden in it.

Simko was also in contact with Kurdish revolutionaries such as Seyyed Taha Gilani (grandson of Sheikh Ubeydullah who had revolted against Iran in the 1880s). Seyyed Taha was a Kurdish nationalist who was conducting propaganda among the Iranian Kurds for the union of Iranian Kurdistan and Turkish Kurdistanin an independent state.

Jointly with Ottoman forces he organized the massacre in Haftevan in February 1915 during which 700–800 Armenians and Assyrians were murdered.

Simko Shikak revolt

In March 1918, under the pretext of meeting for the purpose of cooperation, Simko arranged the assassination of the Assyrian Church of the Eastpatriarch, Mar Shimun XIX Benyamin, ambushing him and his 150 guards, as Mar Shimun was entering his carriage. The patriarchal ring was stolen at this time and the body of the patriarch was only recovered hours later, according to the eye-witness account of Daniel d-Malik Ismael.

On March 16 after the murder of Mar Shimun, Assyrians under the command of Malik Khoshabaand Petros Elia of Baz attacked Simkos’ fortress in Charah in which Simko was decisively defeated. The fortress of Charah had never been conquered previously despite attempts by Iranians and the river was red from the blood of dead Shikak fighters. Simko was panic stricken during the battle and managed to escape, abandoning his men.

By summer 1918, Simko had established his authority in the region west of Lake Urmia.

At this time, government in Tehran tried to reach an agreement with Simko on the basis of limited Kurdish autonomy. Simko had organized a strong Kurdish army which was much stronger than Iranian government forces. Since the central government could not control his activities, he continued to expand the area under his control and by 1922, cities of Baneh and Sardasht were under his administration.

In the battle of sari Taj in 1922, Simko’s forces could not resist the Iranian Army’s onslaught in the region of Salmas and were finally defeated and the castle of Chari was occupied. The strength of the Iranian Army force dispatched against Simko was 10,000 soldiers.

Legacy

In the recent period of Kurdish history, a crucial point is defining the nature of the rebellions from the end of the 19th and up to the 20th century―from Sheikh Ubaydullah’s revolt to Simko’s (Simitko) mutiny. The overall labelling of these events as manifestations of the Kurdish national-liberation struggle against Turkish or Iranian suppressors is an essential element of the Kurdish identity-makers’ ideology. (…) With the Kurdish conglomeration, as I said above, far from being a homogeneous entity―either ethnically, culturally, or linguistically (see above, fn. 5; also fn. 14 below)―the basic component of the national doctrine of the Kurdish identity-makers has always remained the idea of the unified image of one nation, endowed respectively with one language and one culture. The chimerical idea of this imagined unity has become further the fundament of Kurdish identity-making, resulting in the creation of fantastic ethnic and cultural prehistory, perversion of historical facts, falsification of linguistic data, etc. (for recent Western views on Kurdish identity, see Atabaki/Dorleijn 1990).

On the other hand, Reza Shah‘s military victory over Simko and Turkic tribal leaders initiated a repressive era toward non-Persian minorities. In a nationalistic perspective, Simko’s revolt is described as an attempt to build a Kurdish tribal alliance in support of independence.According to Kamal Soleimani, Simko Shikak can be located “within the confines of Kurdish ethno-nationalism”. According to the political scientist Hamid Ahmadi:

Though Reza Shah’s armed confrontation with tribal leaders in different parts of Iran was interpreted as an example of ethnic conflict and ethnic suppression by the Iranian state, the fact is that it was more a conflict between the modern state and traditional socio-political structure of pre-modern era and had less to do with the question of ethnicity and ethnic conflict. While some Marxist political activists (see Nābdel 1977) and ethno-nationalist intellectuals of different Iranian groups (Ghassemlou 1965; Hosseinbor 1984; Asgharzadeh 2007) have introduced this confrontation as a result of Reza Shah’s ethnocentric policies, no valid documents have been presented to prove this argument. Recent documentary studies (Borzū’ī 1999; Zand-Moqaddam 1992; Jalālī 2001) convincingly show that Reza Shah’s confrontation with Baluch Dust Mohammad Khan, Kurdish Simko and Arab Sheikh Khaz‘alhave merely been the manifestation of state-tribe antagonism and nothing else. (…) While the Kurdish ethno-nationalist authors and commentators have tried to construct the image of a nationalist hero out of him, the local Kurdish primary sources reflect just the opposite, showing he was widely hated by many ordinary and peasant Kurds who suffered his brutal suppression of Kurdish settlements and villages.

History of Kurdistan

History of Kurdistan